The overall human population around the world uses 7,168 languages1. Approximately 88 percent of people use 3 percent of the languages. Those languages constitute the dominant languages that are used in government, media, churches, internet, etc. and can sustain themselves for the foreseeable future. Conversely, about 12 percent of the people in the world use 97 percent of the world’s languages. These are generally referred to as minority languages because of the relatively small population of each language group. They represent about one billion people on the planet.

Irrespective of its status or prestige, each language represents somebody’s mother tongue. By this, I mean the first language through which they have been exposed to the world. It informs their sense of identity and provides them with the cultural categories by which they view the world and engage in it. In the words of Dietrich Westermann, the mother tongue is “the most adequate exponent of the soul of a people…. By taking away a people’s language, we cripple and destroy its soul and kill its mental individuality”.2

In the 21st century, the world has been characterized as ‘flat’ because of the rise of the internet, media, and people movement around the globe. However, I still observe that the language that a person uses has the potential to limit or to expand their possibilities to thrive in all domains of life, including the experience of the Christian faith.

Three decades ago, I participated in a research project on the languages of the Western coastal region of Cameroon. I discovered a language group called Bakoko, which was very different from its neighbors. These neighboring communities had a long tradition of the Church using their languages. Their people had found better socio-economic prospects and had a stronger sense of participation in the overall national life.

In comparison, the Bakoko people seemed behind. When I inquired about this, I was told that the people chose to resist the missionaries’ attempts to reduce their language to writing and to translate God’s Word into it. They claimed that their language should be used to preserve the secrets of witchcraft and magic, avoiding any form of corruption. This decision had several consequences for the Bakoko people including hindering their access to the light of God’s Word and limiting their opportunities to thrive.

About fifteen years ago, the Bakoko alphabet was created. Several community members gathered to launch and celebrate the creation of their writing system. The advent of this alphabet gave people the hope that they would be able to preserve in writing their ancestral knowledge and wisdom in order to transmit it to other generations. They would be able to create literature, and to increase and own any relevant knowledge that would further their flourishing as individuals and community.

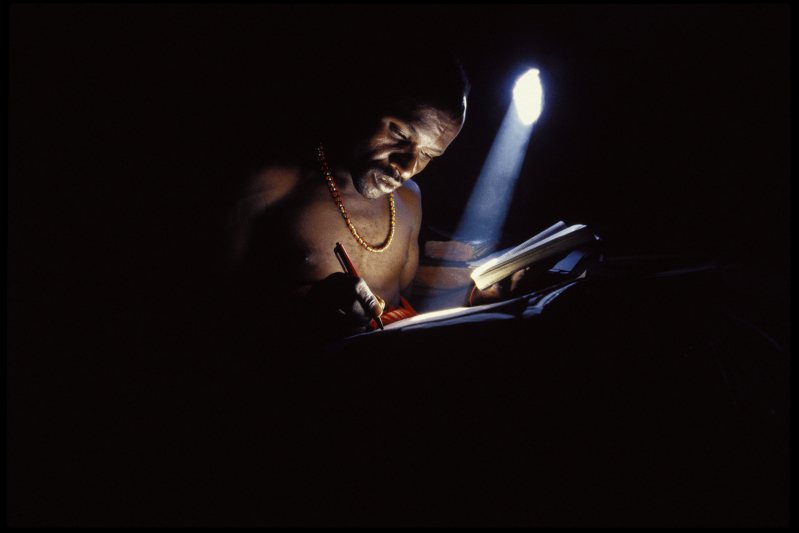

When the first demonstration of the Bakoko writing system’s use was made in public, an old man named Dinjeke burst into tears. When asked later why he got so emotional, he explained the humiliation that he and his Bakoko people had suffered for decades. While the other two major languages of the region had been written and had the Scriptures translated, Bakoko had never received any attention. As a result, evangelisation among the Bakoko people was done in the neighboring Bassa language.

One day when he was a young adult, Dinjeke was asked to pray during the church service. Breaking the church tradition, he stood up and prayed in his native Bakoko language. While he was standing and praying, somebody rebuked him from the back, telling him to shut up and sit down. Following that, the church leadership warned him to never use his mother tongue again in the context of worship. Dinjeke was hurt in his innermost being.

He lived the ensuing decades with shame, feeling that the Bakoko people were undeserving of the same dignity as other people. For this reason, the development of a writing system for his language was more than a scientific achievement. It was a symbolic affirmation that speakers of this language are not second-class citizens of the world. And it planted seeds of the hope that his people might someday enjoy the same prestige as others, using their God-given language.

Today, the New Testament has been translated into Bakoko, bearing the promise to cancel the long-standing plan of their ancestors to hold the people in the realm of witchcraft and magic. Seeing the first copy of God’s Word, one man declared: “Like Simeon in the Bible, I can now rest in peace because my eyes have seen the salvation of my people”. Another stated: “From now on, nothing will hinder the spread of the gospel among the Bakoko people. God is with us. He hears even our deepest sighs.”

Developing a language is not solely an academic enterprise, as the Bakoko experience vividly demonstrates. It is, rather, the key that unlocks possibilities for its speakers to access God’s Word.

It also expands the possibilities for peoples of any language to flourish in all other domains of their life. John Watters,3 a linguistic researcher, noted the following characteristics of the peoples who use the world’s minority languages. They are:

- Economically – most often among the poorest

- Medically – most often in the bottom 20% of those receiving service

- Politically – most often among the most disenfranchised

- Socially – most often among the least valued

- Educationally – most often among the least educated

- Justice-wise – most often among the least informed of their rights and privileges

- Human dignity – most often the least honored or considered worthy.

Taking just one item from that list, consider how language can limit the education prospects of children among minority language communities. Consider Eken, a boy from the Bayangam village in the West region of Cameroon. He spoke only Ghomala’, his mother tongue, until he reached school age. Like all children in the community, he was fluent: he could count and tell the stories that he had heard in his family context. As such, he was confident because he had a clear frame of reference in life. Upon entering the classroom, however, Eken, along with all other children in the community, was exposed to French, a foreign language that neither he nor they spoke or understood. Worse still, speaking the mother tongue on the school campus was forbidden.

For Eken and many like him, this is a traumatic experience — learning both the skills of reading and writing and the language of instruction itself at the same time. To these children, education is not a process of going from what they know to a gradual discovery of the unknown. Rather, it radically and abruptly disrupts their daily life, turning education into a painful and sudden adjustment to a foreign and mysterious reality. As such, education violently disconnects children from their community.

Eken and others like him are obliged to forfeit their identity throughout the education process. It is not surprising that many children like Eken are thought to be unintelligent, and the majority eventually drop out of the school system. It remains a miracle that a few in the community did go through such an arduous system and eventually learned to read and write. However, the majority missed the possibility to achieve their full potential in life. Such people constitute the critical mass of the population whose job opportunities are significantly limited. Hence they see themselves as second-class citizens in contrast to the minority of those who are able to make it through the arduous education system.

As both these examples portray, language is a primary — but too often overlooked — factor accounting for the inability of many to seize the opportunities that would enable them to thrive. In many cases, the best way to achieve the betterment of the people who use the world’s minority languages is to enable their own languages to become the bridge that allows them to improve their economic condition, access healthcare and information, participate in the political life of their nation, restore their dignity as people with equal worth in the world, and enjoy their inalienable human rights. Chief among these rights is the freedom to hear God speak to them directly, without intermediaries, and to respond to him in the language and cultural categories that express their unique perspectives in the world.

Michel Kenmogne is the executive director of SIL International. Born in Cameroon, Michel grew up speaking Ghomalá but was required to learn French when he started school. He holds several degrees, including a doctorate in African linguistics from the University of Buea in Cameroon. He longs to see everyone able to use the languages they value most to flourish. Michel and his wife, Laure Angèle, have five children and live in Kandern, Germany.

1 7,168 living languages according to Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/

2 Diedrich Westermann as quoted by Sanneh, Disciples of all Nations, pp.178-9.

3 Watters, John R. The State of Minority Languages in the 21st Century: in praise of language, in search of compassion. Unpublished paper, SIL International, March 2013, 11-12.